Music Therapy: From Apollo in Ancient Greece to Hospital Rooms Today

Anecdotal instances of music being “therapeutic” can be pointed to by most people. In one way or another, music has impacted our lives - almost everyone we know has had moments where the right song at the right time has improved a mood, helped repair a relationship, or even uncovered an insight that helped shape our personalities.

Beyond these meaningful but non-scientific personal anecdotes, there is an extensive history of real scientific literature on the effectiveness of music for wellness and it's ability to improve the quality of life for a host of conditions and illnesses including autism, dementia, heart disease, Alzheimer’s, depression, and even amongst cancer-stricken or terminally ill patients.

The term for this is music therapy, and it isn’t a hidden idea: in the last 5 years alone, more than 20,000 scientific papers studying or reviewing music therapy as a mode of treatment have been published by academics at institutions such as Johns Hopkins, the National Institutes of Health, and Harvard University.

One important point is that the way music therapy works isn’t just to facilitate temporary surface emotions - music in a proper therapeutic setting with trained professionals can work at a deep level, providing powerful and persistent relief far beyond what you might expect. And - in contrast to virtually all pharmaceutical or invasive medical approaches - there are zero side effects.

The History

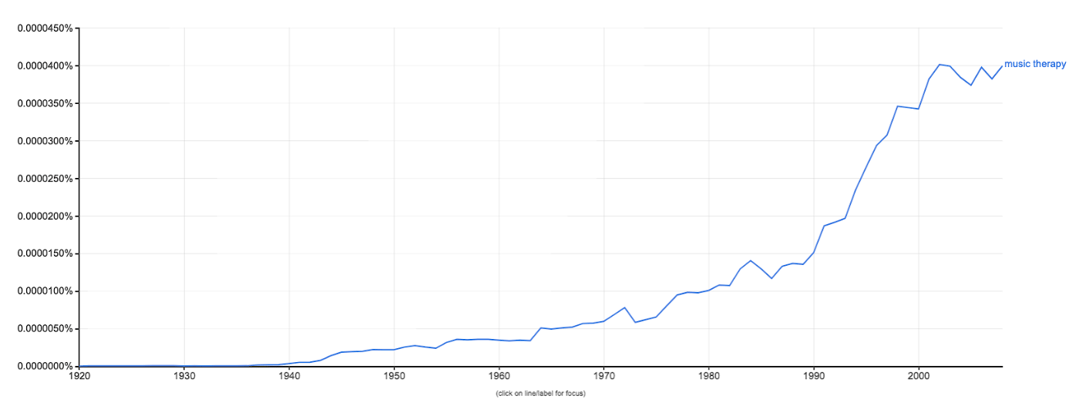

Although music as a source of healing has been in the human consciousness for thousands of years - the Greek deity Apollo was the god of both music and medicine - the formal term “music therapy” didn’t exist until just after World War I, when musicians would travel between hospitals across the European continent to perform for soldiers recovering from battle. From the early 1920s to the 2000s, the rise of the phrase ‘music therapy’ in English-language publications was exponential:

Today, the average citizen seems to be generally aware of the fact that music therapy exists, if not necessarily familiar with how widespread the practice is. Multiple U.S. military facilities offer music therapy to enlisted officers and their families; there is an American Music Therapy Association dating back to the mid-1900s that credentials music therapy practitioners, publishes two prestigious academic journals and counts more than 3,800 active members.

The key takeaway here is: music therapy is a real thing, it’s been studied for decades, and professionals and academics the world over have proven its effectiveness with a wide variety of populations.

The Effects

As mentioned previously, music therapy is one of the most well-documented forms of treatment in modern medicine. Some research highlights are below:

- Schizophrenia: Music therapy significantly diminished patients’ negative symptoms, increased their ability to converse with others, reduced their social isolation, and increased their level of interest in external events.

- Depression: Adolescents listening to music experienced a significant decrease in stress hormone (cortisol) levels, and most adolescents shifted toward left frontal EEG activation (associated with positive affect).

- Insomnia: Positive effects of "Music of the Brain" were evaluated in patients with insomnia in more than 80% cases. These effects were marked on the basis of both subjective feeling and objective (psychological and neurophysiological) results.

- Back pain: Music therapy has been found to decrease pain in patients recovering from spine surgery, compared to a control group of patients who received standard postoperative care alone. The study, published in The American Journal of Orthopedics, included a team of researchers from The Louis Armstrong Center for Music and Medicine and the Mount Sinai Department of Orthopaedics.

Sophia Shu Wang, a violinist and music therapist with the Continuum Care Hospice in Pleasanton, California, says “music therapy is helpful to as many populations as medical care is. Whether children with autism or terminal-care patients in hospital wards, music therapy is used as a balm to ease the burden of whatever a patient may be going through. My work involves healing care - for patients temporarily under medical supervision - as well as hospice care, for those terminal patients who simply need comfort and easement.”

“The method of ‘therapy’ doesn’t imply a passive state on the part of the patient,” Wang adds. “[I] also deliver therapy in the form of participative instrumentation by the patient - we’ll bring them instruments and ask them to play along even if they have no musical experience - assuming they are physically capable, of course - and being involved in the creative process gives a sense of satisfaction and joy that helps with the healing process.”

How Music Therapy Works

Some effects are transferable from outside a medical context: with the general population, music has been shown to improve heart rate, reduce blood pressure, and decrease anxiety. These effects hold true for patients facing serious health issues.

In August 2019, two British professors published a paper in the journal Frontiers in Psychology suggesting that the link between the practitioner and the patient is critical in achieving breakthroughs in treatment effectiveness. The authors cross-referenced a joint electroencephalogram (EEG) (which measures brain activity for the music therapist and the patient) with codified transcripts that identified subjective “moments of importance” during a music therapy session.

The findings were striking: combining both sources of data, the paper’s authors could triangulate specific moments of brain activity that represented definitive transformation in the perceived effectiveness of music therapy treatment. In simpler words, there is an ‘a-ha!’ moment where the patient realizes the therapy is making them feel better. As you can imagine, for patients facing serious illnesses and the emotional tax that accompanies such diagnoses, this realization and the consequent enthusiasm for musical therapy is as important as the cellular effects of the therapy itself.

Other rationales are simpler: Lorrie Kubicek, a practicing music therapist at Massachusetts General Hospital, says that the reduction in perceived pain for patients undergoing music therapy is essentially distraction-based: “Your brain can only perceive 100 percent of any one thing… if you really focus your brain on music it can decrease by 50 percent the amount of pain you feel.” She added that in cases of extreme pain, a patient may not be able to focus on music at all, but most circumstances allow for reduction of perceived pain on account of re-allocating mental energy to focus on music.

Additional beneficial effects are related to the ‘positive expectations’. For patients who are bedridden or otherwise confined to a hospital bed, in-person musical therapy is a rare form of entertainment that is difficult to replicate. The positive feelings associated with a visitor, the feel of live music, and the knowledge that this music positively affects their vital signs builds towards reduced stress and anxiety, and an overall increase in the quality of life for someone facing round-the-clock pain, fear and discomfort.

This last component - the positive emotions associated with the continued exposure to music therapy - links most closely to our own research. On our Feed.fm blog, we’ve previously discussed mood and energy, and how music curation can help workout effectiveness. Whether it’s a family helping lessen the blow of a serious illness or someone trying to conquer a specific Crossfit circuit, music is a powerful ally.

Image Credits: istock.com/baona

2 min

2 min